As I write this, I am less than 200 miles from Panama where I will commence a whole new adventure by traversing the Panama Canal.

Before I get there though, I have a few more thoughts I’d like to share on my time in the Galapagos, and then I’d like to hand-off to our colleague Tegan Mortimer, who here below will share with us yet another in her wondrous series of “Science Notes” (See them all here) – this new one on the Galapagos, naturally… as seen through the awesome lens of science!

While I have talked about my initial visit to the Charles Darwin Research Station, and my subsequent visit to North Seymour Island … not to mention my close encounter of the near disastrous kind … my time on the Galapagos Islands also gave me the opportunity to meet quite a few interesting people and to learn something about their particularly unique and passionate pursuits.

While combing the cafés of Santa Cruz in the evenings, I met turtle experts, tour guides, and other global citizens not so different from myself… as well as several scientist/sailors who were researching local sea life.

On interesting encounter was with a crew member from the Sea Shepherd organization, widely known for their activist opposition to commercial whaling, who educated me as to some of the organization’s less publicized efforts. As regards the Galapagos specifically, Sea Shepherd had given assistance to local authorities in two different areas; the first was in providing trained sniffing dogs to detect the illegal smuggling of exotic pets like iguanas or sea cucumbers, and secondly, by providing local commercial fishermen with AIS (Automatic Identification System) transmitters so that the authorities, as well as other local fishermen operating legally, could better enforce fishing regulations in their territorial waters and thus better promote the health and vitality of the regional fishing stock.

As Tegan explains in her report, there are a variety of research projects going on in the Galapagos. She talks about one that our colleagues at Earthwatch are undertaking with the island’s “famous” finches. When we get to Panama, we will be close to another great Earthwatch Research project – this one involved in safeguarding whales and dolphins in a still remote southern bay of Western Costa Rica – with the intent of protecting them when tourism starts to expand in that area.

While the Galapagos are a special place that has in recent times become a “hot” destination for the eco-tourism industry, the fact is that places just like the Galapagos exist in one form or another just about everywhere in the world. Most, if not all of these under-developed areas are under similar pressures to stand up under the excessive burdens put upon the local environment and their populations.

While the Galapagos are a special place that has in recent times become a “hot” destination for the eco-tourism industry, the fact is that places just like the Galapagos exist in one form or another just about everywhere in the world. Most, if not all of these under-developed areas are under similar pressures to stand up under the excessive burdens put upon the local environment and their populations.

Think about the Galapagos going from 600 residents to 20,000 in less than four decades while at the same time trying to accommodate the growing stream of tourists that comre and all of whom need food, lodging and services. Imagine the effect this has on indigenous populations, which can be easily overwhelmed by such demands.

One last memory of the Galapagos I would like to share. Last week at the end of a long day working on the boat and in the rain… I found myself growing increasingly frustrated with how long it was taking to coordinate and schedule thing with local services. Suddenly, some elusive mental puzzle piece just magically fell into place – and I knew I had to take a walk to Turtle Bay – some 40 minutes away. I had only an hour before public access to the beach was to close, so I hurried off.

The hike took me through a broad patch of cactus and trees, then through low brush and across lava fields at which point, l cleared a rise where ahead of me opened up one of the cleanest and longest stretches of white sand beach I have ever seen.

With only a few moments until I had to turn around and walk back, I sat in the sand and watched as surfers rode the waves, hikers walked along the beach, photographers with extra long lenses looked for epic photographs and ghost crabs played tag with the waves and with each other. In just a few minutes’ time, all the frustrations of the day evaporated, and I was tucked under nature’s wing … preserved there at the shifting border between sea and shore.

Turtle Beach – Santa Cruz Island – Galapagos

It struck me in that moment how very important it is that places such as Turtle Beach be allowed to exist – specifically such places that still ROAR with a natural beauty that has not yet been compromised and transformed by commercial development or resource extraction

How can we keep these places as natural and undisturbed as possible yet still allow them to be publicly available to all? How can we maintain their raw and yet fragile beauty so that they might remain pristine for generations to come?

It’s places like Turtle Bay that serve to keep us in touch with our natural world – and with our natural selves! We are not separate from the natural world. Rather we are an absolutely integral part of it – the world’s fate is our fate. As the great Henry David Thoreau famously wrote… ”In wildness is the preservation of the world.”

As the miles click off behind me and I near my transit of the Panama Canal, I come to the close of my time traversing the Pacific Ocean. I know that the crossing of the Canal will be another amazing experience and of an entirely different nature than that any that has came before it… but an experience entirely new and unexpected I know it will be… which is what I have only recently learned… is what people like myself awaken each morning intent upon experiencing.

– Dave, Bodacious Dream and (the ready-for-anything) Franklin

________________________________________________________________________

:: Tegan’s Science Notes #9 – The Galapagos

Sailors called them the Enchanted Isles because strong currents and swirling mists could cause the islands to disappear and reappear right before their eyes. The Galápagos were made famous by Charles Darwin’s visit in 1835 during his voyage on board the HMS Beagle. The observations Darwin made on the islands had a direct impact on the development of his theory of evolution. Today these islands are still an unmatched source of biological wonder and continue to contribute to our study and understanding of the process of evolution.

Sailors called them the Enchanted Isles because strong currents and swirling mists could cause the islands to disappear and reappear right before their eyes. The Galápagos were made famous by Charles Darwin’s visit in 1835 during his voyage on board the HMS Beagle. The observations Darwin made on the islands had a direct impact on the development of his theory of evolution. Today these islands are still an unmatched source of biological wonder and continue to contribute to our study and understanding of the process of evolution.

Despite straddling the equator, the Galápagos do not have a tropical feel. In fact this archipelago is home to the northernmost penguin colony in the world, the only native penguins to be found in the Northern Hemisphere (though the penguins do spend most their time in the Southern Hemisphere just below the equator). You’ll remember from my African Penguins post (if you haven’t read it yet, you can find on the Citizen Science tab) that the key is in the water: cold, nutrient-rich water.

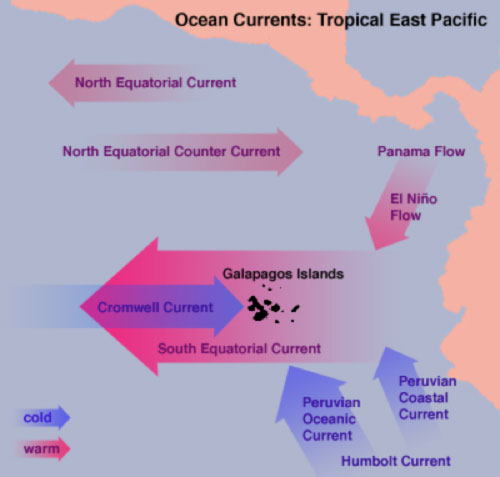

The Galápagos Islands are located in a unique area in which can be found the convergence of several currents of tropical and subtropical waters that upwell around the islands. For a long time oceanographers thought that the cold waters surrounding the Galápagos came from the Humboldt Current (also known as the Peru Coastal Current) which runs along the western coast of South America carrying cold Antarctic water. However another type of current, called an undercurrent, which runs below and opposite to a surface current, was discovered in 1956. This current, called the Equatorial Undercurrent or Cromwell Current after its discover, is now seen as the reason for the island’s cool waters. The Cromwell Current flows eastward the entire length of the equator in the Pacific Ocean at a depth of about 100m below the westward flowing surface currents. As the current approaches the Galápagos, it is forced upwards by underwater seamounts forming an upwelling system. The waters then flow westward again as part of the South Equatorial Current.

There is a reason why Darwin’s visit to the Galápagos (as well as other islands) had such an effect on his ideas about evolution and natural selection. Islands often have a large number of endemic species, i.e., those that are found nowhere else. The Galápagos are no exception to this. But why do islands have so many unique animals? Geologically, the Galápagos are fairly young, they are volcanic islands formed sometime between 8 and 90 million years ago. In that time animals had to colonize the newly formed islands from the closest land, which is the mainland of South America, over 500 miles away. Of all the animal colonizers that reached the Galápagos only a few would be able to survive and establish populations, which are the animals that still survive today.

When animals colonize islands, a few things often happen. These animals have been ‘released’ from pressures like competition and predation that they were under in their original locale. so they can quickly diversify to take advantage of the many different ecological niches that are available in their new home. These animals often don’t have to worry about predators any longer so they lose many of their anti-predator behaviors. Dave’s story about the baby sea lion illustrates this very point. The parent seals can leave the babies alone while they go hunting, knowing that no predator will attack the vulnerable babies. It may also help explain why the baby sea lion in Dave’s story came right up to the tour group without any hesitation. Among birds, this absence of predators can account for why birds may become flightless or lay their eggs on the ground, just as the blue-footed booby does.

These traits make islands very susceptible to the effects that follow from introducing animals like cats, dogs and rats which can easily prey on native animals. Humans too have had a heavy impact on island populations by hunting some animals to extinction. Luckily, today we have come to realize just how fragile these ecosystems are which has caused many people to take up the work of protecting such special and “endangered” places… including the Galápagos.

Darwin’s Finches

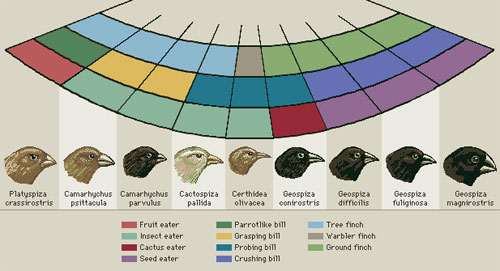

There’s one group of animals from the Galápagos that needs a special mention. Darwin’s finches are a group of 15 species of birds found throughout the islands which Darwin specifically mentions in his Origin of Species. In this way, these birds became an important part of the scientific history of evolutionary thought, and as I will explain still have an important role in our modern understanding of evolution and the ways humans can impact it.

These birds are the classic example the adaptive radiation I mentioned earlier. A colonizer species to the island, the finches diversified into these 15 species all of which have different shaped beaks, which are based on what type of food that particular species eats. These birds are thought to be the fastest evolving animals on earth which means that researchers can follow them, year to year, and track the natural selection pressures which define which species thrive and which do not.

However another pressure is being placed on them as well. Human foods, like rice, are now widely available in much of these finches’ range. Birds that feed on human foods can lose the characteristics that make them evolutionary ‘fit,’ as earlier selection pressures are no longer being placed on them. The loss of these characteristics can erode the differences between the various species of finches leading to a loss of biodiversity. So instead of 15 different species, which are highly evolved to eat different food sources, we may end up with just a few species that feed on human scraps. It would be tragic loss of such an amazing group of birds.

This is actually a research project that Earthwatch is conducting in the Galapagos right around where Dave moored Bodacious Dream. You can find out more about there project called Following Darwin’s Finches in the Galapagos at the link.

– Tegan

:: For more exciting science insights and opportunities, please check out our BDX Explorer Guides or stop by our Citizen Science Resources page, where you can also find all of Tegan’s previous Science Notes, Also, we welcome your input or participation to our BDX Learning and Discovery efforts. You can always reach us at … <oceanexplorer@bodaciousdreamexpeditions.com>

:: BDX Website :: Email List Sign-Up :: Explorer Guides :: BDX Facebook