Sailing Navigation: Expert Interviews with John Hoskins and Matt Scharl

Interviewed by Dave Rearick, Skipper of Bodacious Dream

See two other expert interviews Dave has conducted:

:: Rigging Technology – an interview w/ Alan Veenstra

:: Composite Materials Technologies – an interview w/ Lapo Ancillotti

:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Dave Rearick: In an effort to explain the principals of navigating a sailboat across vast stretches of water and around race courses, I’ve asked two good friends and fellow sailors to help explain those principals and what fun they’ve had with them through their years of sailing.

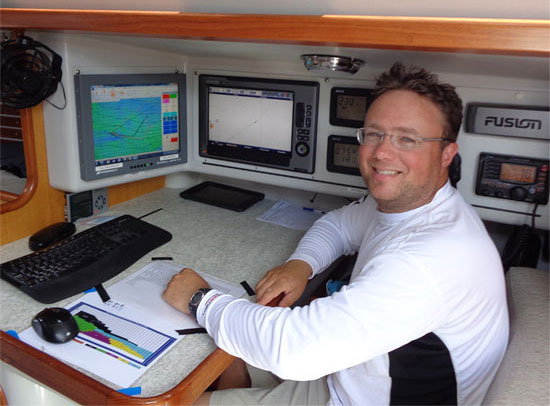

First off, I’d like to introduce you to John Hoskins, who has navigated for the Bodacious Racing program since 2008. He will explain the principals of navigation and the equipment he uses to help him succeed.

Secondly, meet Matt Scharl, my co-skipper in the offshore legs of the Atlantic Cup on Bodacious Dream in 2012 where we finished second and again in 2013, where we won overall honors. Matt will explain the complexity of racing the Atlantic Cup race course from Charleston, South Carolina to New York City and then from NYC to the turn mark off New Jersey and back up past Block Island to the finish in Newport Rhode Island.

I. John Hoskins | ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Dave Rearick (DR): John, you navigate for Bodacious IV, the Santa Cruz 52 that we crew raced around North America. Bodacious IV has a pretty sophisticated navigation system onboard, but all navigation comes back to the simple principals of triangulation. Can you tell us more about the basics of triangulation?

Dave Rearick (DR): John, you navigate for Bodacious IV, the Santa Cruz 52 that we crew raced around North America. Bodacious IV has a pretty sophisticated navigation system onboard, but all navigation comes back to the simple principals of triangulation. Can you tell us more about the basics of triangulation?

John Hoskins (JH): Triangulation is when you cross two directional lines from known landmarks and the intersection is where you are. In the early days, you would use a compass and take a direction on two known landmarks, maybe a lighthouse and a point of land… and then draw those compass degree lines on a chart, and where the lines crossed would be where you are. For instance, say the lighthouse is at a compass bearing of 090 degrees and the point of land is at 180 degrees. You would draw two lines from each of these points on the angle of the compass degree, and where they crossed would be your location. This is the basics of navigation. As navigation grew more sophisticated, navigators used sextants to get lines of triangulation from the stars. And these days, in the more sophisticated technological world, these same principals apply, but just done more quickly and efficiently using satellites (somewhat like man-made stars) and computers. Today this is referred to as GPS navigation. You find this technology in many areas now—your phone, your car and even in warehousing to locate items by robots.

John Hoskins (JH): Triangulation is when you cross two directional lines from known landmarks and the intersection is where you are. In the early days, you would use a compass and take a direction on two known landmarks, maybe a lighthouse and a point of land… and then draw those compass degree lines on a chart, and where the lines crossed would be where you are. For instance, say the lighthouse is at a compass bearing of 090 degrees and the point of land is at 180 degrees. You would draw two lines from each of these points on the angle of the compass degree, and where they crossed would be your location. This is the basics of navigation. As navigation grew more sophisticated, navigators used sextants to get lines of triangulation from the stars. And these days, in the more sophisticated technological world, these same principals apply, but just done more quickly and efficiently using satellites (somewhat like man-made stars) and computers. Today this is referred to as GPS navigation. You find this technology in many areas now—your phone, your car and even in warehousing to locate items by robots.

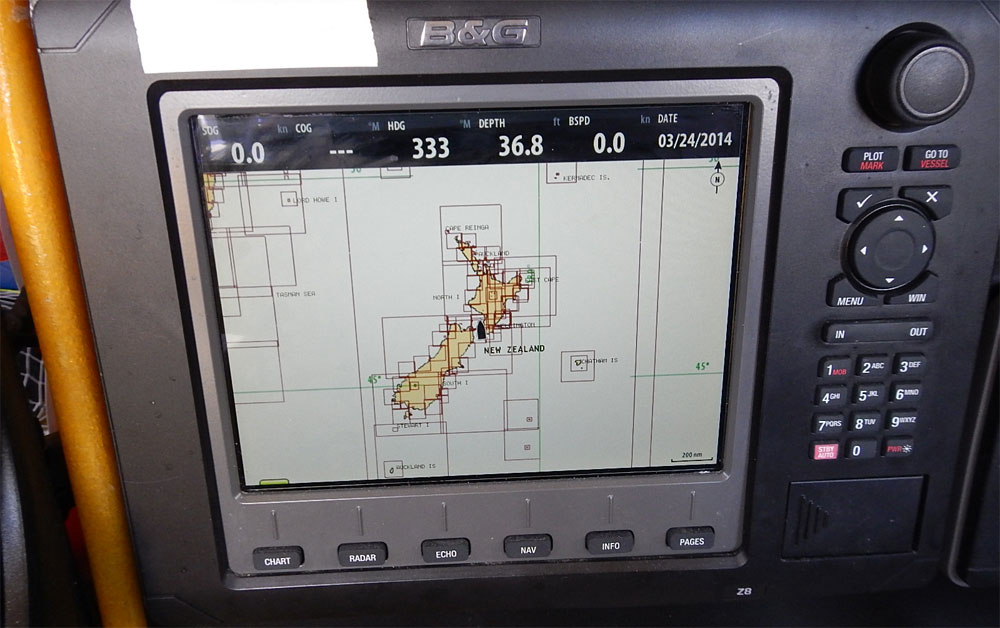

DR: Can you tell us a bit about the electronic instruments you use for navigation?

JH: The GPS of course is tied into a host of things… a chart plotter, (this is a computer-like monitor with nautical charts imbedded in it), the wind instruments, sea temperatures, an automatic identification system (AIS), expedition navigation software, and the uplink Sailor 250 satellite for access to the Internet for GRIB files, that store tide and weather information.

DR: Its sounds like in addition to the GPS location data, you also have a lot of information about the weather and the conditions into which you are sailing? How often do you monitor these conditions and re-plot your position?

JH: I am constantly analyzing weather data as new data comes to the boat via GRIB files and satellite images about every two hours. With that information I will adjust or confirm the direction we are sailing and the waypoint we are sailing towards. That waypoint is a position on the racecourse that will optimize the course to the best weather conditions for our boat – which is not always the most direct route to the finish, but rather the most efficient course to sail. The waypoint is usually 2-4 days out. On longer races like the TransPac, the waypoint is not the finish, but rather a set of points between our current position and the finish. Much further away than that, the weather data is not as accurate.

DR: Do you still use paper charts?

JH: Yes I do. I plot our position at regular intervals as a backup if our electronics go out. They’re also required safety equipment by most race committees.

DR: When you mention wind instruments, what are these and how do they work?

JH: The wind instruments are sensors at the top of the mast that measure wind direction and wind speed. The information from these instruments helps the crew trim the sails, drive the boat as well as help me analyze our current wind conditions. Good calibration of the wind and boat speed sensors is critical for our performance analysis and projections using our Expedition software.

Wind instruments at the top of Bodacious Dream’s mast

Wind instruments at the top of Bodacious Dream’s mast

(Note: More detail on the instruments, there are two sensors at the mast top. One senses and communicates direction and sends down three different signals which a computer crunches into a compass direction for the wind. The second is spinning and as it spins faster, it sends a signal to the computer processor indicating wind strength. The processor then takes all this information along with boat speed and compass heading and instantly puts it through various calculations to present to the navigator and sailors information such as apparent wind speed (that which you feel on your face which can be a combination of the wind speed and boat speed), apparent wind angle, true wind speed and true wind angle as well as true wind direction magnetic and more complex numbers such as velocity made good, drift and set of currents.)

Slideshow – Click arrows to advance! Scroll over to read descriptions.DR: So John, when you have all this information at your fingertips, what do you do with it and what is your goal?

JH: Well… we constantly monitor the information for changes and trends, which we use to adjust our course and maximize our efficiency in sailing. When we are racing, we are looking to sail the shortest distance as fast as we can… however, this isn’t as simple as just that. There are times when it’s faster to sail a longer route than the shorter one… because the speed we sail at on the longer route is faster in the net result than the seemingly shorter route This we call VMC (velocity made good to course.)

DR: Boy, that sure sounds like a lot of headwork. You mentioned Expedition software. How does this help with that?

JH: The Expedition navigation software puts all the information I need together on one computer screen. As it plots our course over electronic charts, it also overlays the forecasted weather. It will plot an optimized course (route) for us based on the weather forecast and how it changes over the course we will sail over a few days. Expedition also records all the information coming off our instruments so that I can analyze historical boat performance and the weather conditions we experienced in the past. It will save this data for the entire race and keep it for reference the next time we do a similar race.

(An Example: Expedition’s optimized route is not always the fastest. While it is a powerful tool for a navigator, it may not pick the best route right away. On the 2013 TransPac, an inverted low-pressure system entered the south side of our racecourse. I slowly positioned the boat south of our competition to have a chance to gybe to it. This was a couple days before Expedition routed us there. It wasn’t until we were committed to head south to the low-pressure system that Expedition started routing us there. For me, it is actually rare that we sail Expeditions exact route, but analyzing the range of Expeditions routes are critical to making good tactical decisions. Expedition is a great tool, but it is no replacement for solid navigation skills.

DR: That’s great stuff John. How long have you been navigating and can you tell me of one of your more memorable successes?

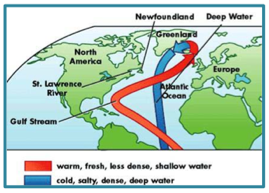

JH: I have been sailing all my life and acting as navigator/tactician on boats since the late 90’s. I have always had a passion for sailing and weather forecasting and that all comes together for me on the racecourse. The technology and access to weather information has changed dramatically over the last 10+ years. It’s been fun learning the latest navigation tools. The most memorable race for me was the Newport to Bermuda race is 2008 with you and our friends on the Bodacious program. We chased a warm eddy off the Gulf Stream very far west and ended up winning our section and placing well in fleet. There are always errors with boat tactics and planning a route, and in that race I think we had very few. We ended up in the right place at the right time and took full advantage of the strong Gulf Stream currents. It was a great race!

II. Matt Scharl | ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::

Dave Rearick (DR): Matt, you handled the navigation for our two years in the Atlantic Cup where we did quite well in the offshore races, taking a third in the first leg two years ago and winning the second and then winning both offshore legs last year. Can you explain the course we race and some of the interesting natural aspects we have to navigate with and around?

Matt Scharl (MS): The first leg of the race is from Charleston, South Carolina up to New York City, about 635 miles. The interesting aspects one considers in this leg are the Gulf Stream, conditions around Cape Hatteras and the general weather systems. The Gulf Stream, which is like a river of north-bound current, is fairly far offshore at Charleston, but comes quite close by the time you reach Hatteras at which point it turns offshore again north of there. The big calculation we have to consider is whether it’s worth the extra distance to go out to the stream early, catching a boost from the two to four knots of current, or to stay along shore and sail less overall miles. Next, as the stream comes close to Hatteras, the currents and the wave can become quite variable and so when to exit the Gulf Stream becomes the big question. Tides along the coast flow in and out every six hours or so, and in the New York City Harbor, these tides create very interesting dynamics and are the third variable on this leg that needs to be analyzed.

Matt Scharl (MS): The first leg of the race is from Charleston, South Carolina up to New York City, about 635 miles. The interesting aspects one considers in this leg are the Gulf Stream, conditions around Cape Hatteras and the general weather systems. The Gulf Stream, which is like a river of north-bound current, is fairly far offshore at Charleston, but comes quite close by the time you reach Hatteras at which point it turns offshore again north of there. The big calculation we have to consider is whether it’s worth the extra distance to go out to the stream early, catching a boost from the two to four knots of current, or to stay along shore and sail less overall miles. Next, as the stream comes close to Hatteras, the currents and the wave can become quite variable and so when to exit the Gulf Stream becomes the big question. Tides along the coast flow in and out every six hours or so, and in the New York City Harbor, these tides create very interesting dynamics and are the third variable on this leg that needs to be analyzed.

The second leg from New York City south to the turning mark off New Jersey and then north to Newport where you encounter Block Island presents you with another major decision as to whether you go east or west of Block Island.

DR: Two years ago, we saw a very unusual thing as we exited the Gulf Stream headed towards NYC. Can you explain why the winds went so weird and why our competitor Mare looked so odd due to the hazy fog?

MS: The Gulf Stream is a river of water that runs through the ocean at a significantly warmer temperature than the surrounding water. It might be hard to believe, but in some places, it’s as noticeable as a river on land. You mentioned the weird look that Mare our competitor had when they exited the Stream. As we got to their location the water temperature dropped over 10 degrees and the wind went very light. What happened there is that the warm air over the Gulf Stream was rising and creating clouds (similar to when you look inland on a beach and see the white puffy clouds forming along the shore). These clouds are created quickly as the air rises, (note that clouds only form when air is rising) creating a pressure difference that causes cooler air to fill in underneath the warm air rising. Mare was outside the stream and had a hazy look, because the marine layer (stagnate air over cold water) was being refracted by the clear, clean air that we were sailing in, until we were in it as well.

MS: The Gulf Stream is a river of water that runs through the ocean at a significantly warmer temperature than the surrounding water. It might be hard to believe, but in some places, it’s as noticeable as a river on land. You mentioned the weird look that Mare our competitor had when they exited the Stream. As we got to their location the water temperature dropped over 10 degrees and the wind went very light. What happened there is that the warm air over the Gulf Stream was rising and creating clouds (similar to when you look inland on a beach and see the white puffy clouds forming along the shore). These clouds are created quickly as the air rises, (note that clouds only form when air is rising) creating a pressure difference that causes cooler air to fill in underneath the warm air rising. Mare was outside the stream and had a hazy look, because the marine layer (stagnate air over cold water) was being refracted by the clear, clean air that we were sailing in, until we were in it as well.

Centuries ago, when navigators didn’t have as many tools as we have nowadays, they would keep note of experiences like these, and when they encountered them again, it reinforced their navigation to help them confirm where they were.

DR: In both years, Block Island presented an interesting obstacle in the middle of the course near the entrance to Narragansett Bay and Newport, Rhode Island. You had to decide whether to go East around the outside or West to the inside of Block Island to get to the finish in Newport. Both years we did the right thing and won those races, but we chose different routes both years. Can you explain what decisions were made there?

MS: Block Island is directly in the middle of the course from New Jersey to Narragansett Bay. Approaching it, the racers have to decide which side to pass it on. Current and wind obviously play important roles in this decision. There are clear norms like when the wind is out of the east, which indicates a clear choice to starboard or west to port. However, when conditions are in between these norms – that makes for challenging times. The first race that we won we were leading and going east of it was a no brainer, because the wind was out of the ENE. The second race was more challenging, we were in third place at that point, the wind was out of the south, and it appeared the boats in front were going to the east of Block Island and we knew that we’d never win following them, but we didn’t want to lose out to the boats behind us by going the wrong way either. Here’s where you meet your decision maker. My gut had been saying go west from the start of the race, we followed my gut instinct, it worked and we came out first. My experience in sailing and life tells me to go with my gut instinct on most decisions.

DR: Gut instincts are very important on the water; they are often developed over years of observations and experiences. You race both multi-hulls and mono-hulls and in all different venues. What has been your most memorable navigational experience in all the sailing you’ve done?

MS: This brings me back to the gut feel side of decision-making. I remember a 285-mile, Port Huron to Mackinac Race on the Great Lakes in the Midwest of the USA. A few hours after the start all the boats in the fleet were starting to go to the right side of the course, as the weather maps and conventional wisdom said that going right was the correct decision, so we too gybed and went that way. I then went below to take a nap, but I couldn’t relax. Things just felt wrong and after a few minutes I came back up on deck to tell the guys I couldn’t go right – that it just felt wrong. They trusted me and we gybed and went the other direction. I then slept well. Fast forward to the end of the race… we won, and not by just a little. Always trust your instincts in life, stay true to your goals and you will prevail.

DR: Like all of us who grew up sailing, we often went looking for rides on boats. I’m sure you did the same things I did. Walking the docks letting people know you were available to crew for a race. Any advice for new sailors looking to get onboard?

MS: Yes, I guess we all did the same things. I used to walk the docks and ask to go on races with the line, “give me one chance, if you don’t like what I do, I won’t bother you again.” It worked for me.