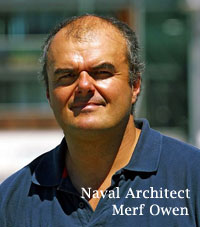

Dave Rearick of Atlantic Cup Kids interviews Merf Owen, Sailor, Naval Architect and Yacht Designer and principal of Owen/Clark Design, LLC.

Dave Rearick (DR): How old are you now Owen, and when did you get interested in sailing?

Merf Owen (MO): I’m 53 and I first started sailing with a sail training organization called the Ocean Youth Club, when I was 16. I was brought up in the middle of England, far from the sea, but before I left school I had decided I would join the Navy, but I’d never been to sea really. So, I thought I had better do some sailing. My first few days at sea were spent in a very famous storm (in Europe) during the Fastnet Race of 1979.

DR: Where is your home office?

MO: I live in Hamble in England, but my company’s office is three hours away in Dartmouth and we also have an office in New Zealand. The Internet is what helps us to all be able to work together and share a working environment and communicate over thousands of miles and many different time zones.

DR: Your work has you travelling and sailing all around the world, how much do you travel?

MO: I spend a lot of time on the West Coast and East Coast of the United States for business and pleasure. In one year I am only in Hamble perhaps 6 months maximum. The rest of the time I’m in the US, Europe and Australia meeting clients, sailing or going to boatyards/conferences etc.

DR: Do you remember a moment in your life where you got your first big sailing break? The first chance to crew on a hot racer, a meeting with a famous sailor or something like that? Can you tell just a bit about how it inspired you?

MO: The first break was sailing with the Ocean Youth Club… it changed my life. My first big break racing was sailing as navigator on the 85’ catamaran Novell Network with an English skipper called Peter Phillips. We took part in the Round Europe Race in 1985. I was twenty two… and inspired by sailing alongside some of the greatest sailors of their generation… Robin Knox Johnston, Phillip Poupon, Serge Madec, Tony Bullimore…. also Peter Phillips himself, who almost won (but came third in the end) in the 1980 Single-handed Transatlantic Race from Plymouth England to Newport RI. He was beaten by Frenchman Phillip Poupon. It was very special to be around these guys on the dock. I thought after this I would be a professional sailor… but I had to make a choice between careers and I chose design and engineering.

DR: I know you sailed the predecessor to the Volvo Ocean Race…

MO: No, I was a skipper on the BT Global Challenge 1996/97, at the time called the Whitbread Race.

DR: What boat did you sail and how did you get the chance to compete in the Whitbread?

MO: My boat was Global Teamwork. I got the chance by applying for the position of skipper with race organiser Sir Chay Blyth, who I knew from my days multihull sailing. Chay had won the double-handed transatlantic race and was the first man to row the Atlantic Ocean. I applied for the job by an email using satellite communication, the same day as I rounded Cape Horn for the first time with another old friend of mine I met racing multihulls. Alan Wyn Thomas. I’m a strong believer that a sailing life and life in general is about meeting people, being stroked by them and stroking others in return. I am from the middle of England, far from the sea, no one in my family sailed and my father was a train driver. I was lucky with the people I met, but I also made the effort to go out and meet people. I think this is important for young people to know: There are a lot of good people out there who will and can help, but you need to go out and not be afraid to ask, get dirty, start at the bottom, and work hard for what you want… that’s the American way too isn’t it?

DR: When did you get interested in Yacht Design and what course of study did you pursue to become a yacht designer?

MO: I left the Navy and put myself through college… to study naval architecture (submarine design actually) with Royal Corps Naval Constructors at University College London. It was during this time, sailing and racing other people’s boats that I began to gain confidence and begin to think that I could design something better than the boats I was sailing.

DR: Are there particular classes a young student should pay particular attention to if they want to pursue yacht design and engineering?

MO: Maths, Physics, computer studies… but you need to get out on the water too. I would never employ a designer/engineer who either does not sail or has not worked as a boat-builder. Yacht design is not just a theoretical engineering subject. One needs passion and the two most passionate types of people I know are boat builders and sailors. Even if you’re not a great engineer/mathematician, there can be a place for you in a yacht design office if you’ve other skills.

DR: In the years you’ve been designing, can you talk us through a simple history of the changes you’ve seen?

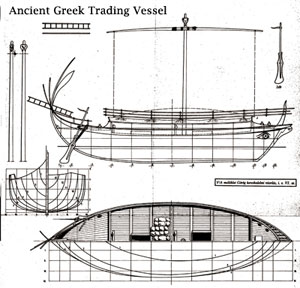

MO:I think the students will find it interesting how far technology has come in the 30 years since I started designing boats at the beginning of the commercial computer age. Although my business partner has ‘drawn’ boats I never have. I used an early Apple computer…an SE to produce the geometry, the line drawings, using an early version of the MaxSurf software that we still use.

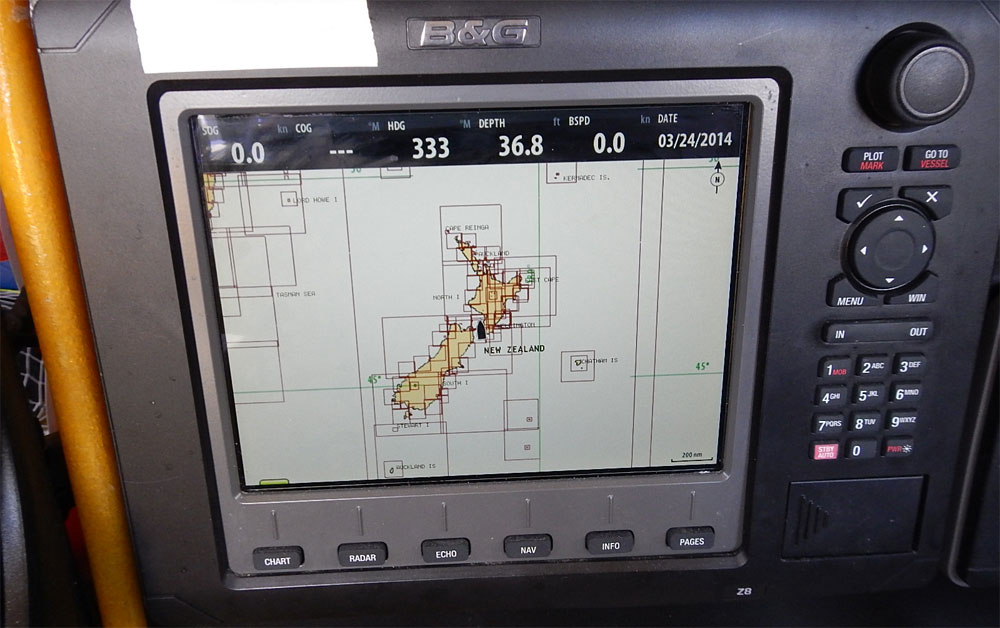

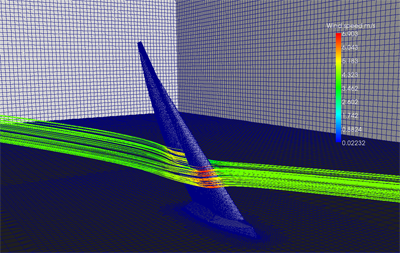

Engineering was undertaken with Lamanal Software using a Sirius computer I bought from a company called SP. It was very advanced at the time and cost a lot of money. It used actual Floppy discs – 5.25 inch which could hold 600 KB of information. Amazing eh? Jumping forward thirty years and my laptop is many times more powerful than the Cray super-computer I used at University to develop software in Fortran 77. Nowadays the performance orientated yacht designer’s armory of hardware and software on our laptops is comprehensive. We have the ability to model using computational fluid dynamics, weather, performance analysis and engineering that only an America’s Cup team would have had even ten years ago.

DR: How many Class 40 designs have you done and how many of your designs are in the Atlantic Cup this year?

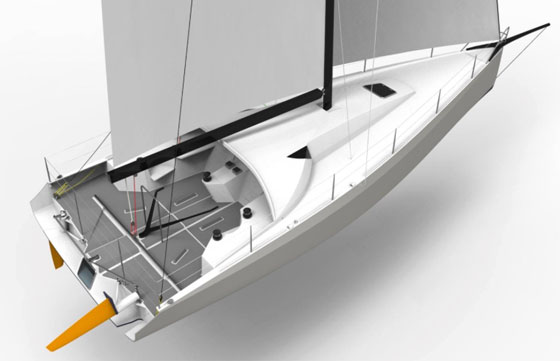

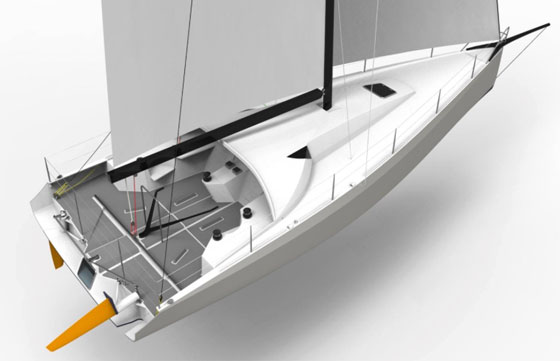

MO: We have just signed a contract on our sixteenth Class 40 that will be built in South Africa. In the Atlantic Cup this year we have two of our boats racing… Dragon, one of our oldest boats, built in 2008 and Longbow, which is a new boat built last year in Rhode Island.

DR: Longbow is your most recent Class 40 design. You designed it specifically for the Atlantic Cup. In simple terms a person without detailed knowledge would notice, what makes it different?

MO: Class 40 began in Europe where the target races are mainly Trans-Atlantic from East to West. Racing sailboats rely on wind to power them. How fast they go, depends on how they perform changes with the different speeds and angles to the wind that they sail. If you sail across the Atlantic from West to East, instead of from West to East, then it’s possible to design a different kind of boat, one that is faster in those winds. Also, on average in the ocean, in the middle of the Atlantic the wind is stronger than it is on the east coast of the United States. Since all the Class 40s designed and built in Europe were designed for the Atlantic Races, we thought it would be a good idea to design Longbow just for the races it will do on the East coast of the USA. The owner of Longbow just wants to race in America, not across the Atlantic… so the boat is specifically designed for the local conditions. It is faster in the light winds that are a feature of sailing in the summer along the Eastern Seaboard between Charleston and Portland.

DR: What do you think makes a boat a good design?

MO: All good sailing boats are easy to sail, hold their direction when sailing with the minimum of input from the sailor/helmsman. We also like our boats to be “pretty”, although beauty is different in the eye of different people. We often use the following phrases when talking with clients/boat builders/journalists. These are phrases that are well-known to describe design, and we are not the first to use them:

“Function follows form…. which means if it looks right, it ‘probably’ is right.”

At the same time as the above, we’re engineers/technicians as well so we also believe that those who fall in love with practice but without science are like a sailor who steers a ship without a helm or compass, and who never can be certain whither they are going. And the great Nat Hereshoff invented a word when he urged designers to: “Simplicate and add lightness.”

DR: Why do the Class 40’s have two rudders when other boats only have one?

MO: Class 40s are so wide that when they heel over in the wind, if they had only one rudder in the middle it would come out of the water and make the boat impossible to steer.

DR: Most people will notice these boats are very wide, what is the reason for this?

MO: Most racing sailboats historically have been designed to a rule that limits the width of the boat and also the performance. Class 40 comes from a genre of design which has a history of unrestricted rule… it’s called “Open Class.” Wider, in general, is faster… so long as there’s enough wind to match the sailplan of the boat and keep it ‘powering along.’

DR: Are the boats considered light for their size?

MO: Yes, they are… not super light because the rule limits their construction to glass fibre… to save cost. They could be lighter if they were built from carbon fibre… nevertheless, compared to your average sailboat, they are light.

DR: How fast can the Class 40’s go?

MO: I have sailed at 22 knots, but I know boats in certain conditions have sailed at 25 knots and even 30 knots… which is 29-35 mph.

DR: What has been the most exciting project you have worked on designing boats?

MO: So many exciting projects and not all of them racing boats… it’s hard to pick one because they’re all exciting and often for different reasons. People you work with also add excitement, as well as the kind of boat. At the moment, we’re working on a high -latitude cruising boat that will visit the Antarctic and the Arctic and it’s built out of aluminium, not carbon fibre. It’s a very exciting project. Of course, my first boat… a 35’ racing trimaran was an amazing project. I’m still best of friends with the three people who helped me build that boat and one of them is my business partner. Kingfisher, our first Open 60 was designed and built in New Zealand for a young girl… Dame Ellen MacArthur (from the middle of England, much like myself). That was an amazing project, both because of the technology and the people. Our eight and most recent Open 60, Acciona was the first racing boat of its type to circumnavigate the Globe without having any carbon/fossil fuels onboard… just solar and water-generated energy… a cool project. And let’s not forget Longbow… a great project, working with good people and a great owner to create a very special and innovative sailboat. It was fun too building her right here in the United States.

DR: I’m sure the computer and CAD drawing has changed your work… what exciting technologies do you hope these young students watching the Atlantic Cup will develop to make the job of yacht designing even easier and boats even better?

MO: 3D printing is beginning to make a difference in how we present projects to a client. Five years ago we were able to use it, at great cost, to show a client what a 40m cruising boat would look like. Today a workable size printer sells for $3000, and we’re just about to buy one for the office. In the future I’m sure we’ll be able to walk clients though a holographic image of a design, either in our office, at the boatyard or at their home. I hope this happens before I retire!

DR: Thanks so much Merf!

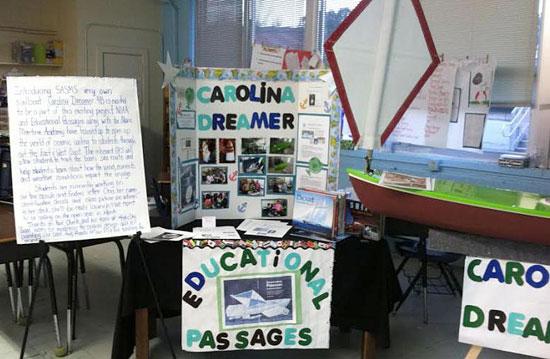

We’re in the thick of it now! With so much to do for the Atlantic Cup Kids program, time has really been flying by quickly. The start of The Atlantic Cup Race is less than 10 days away and our first group of students will be visiting the race village in Charleston, SC a week from now! In Charleston alone, we have scheduled over 500 students to visit the race village and boats! That’s an epic leap forward!

We’re in the thick of it now! With so much to do for the Atlantic Cup Kids program, time has really been flying by quickly. The start of The Atlantic Cup Race is less than 10 days away and our first group of students will be visiting the race village in Charleston, SC a week from now! In Charleston alone, we have scheduled over 500 students to visit the race village and boats! That’s an epic leap forward!

To help me with this, I engaged my friend Merf Owen, a noted naval architect and the designer of two of the boats in the Atlantic Cup to talk about his life and how he came to be a racing yacht designer.

To help me with this, I engaged my friend Merf Owen, a noted naval architect and the designer of two of the boats in the Atlantic Cup to talk about his life and how he came to be a racing yacht designer.

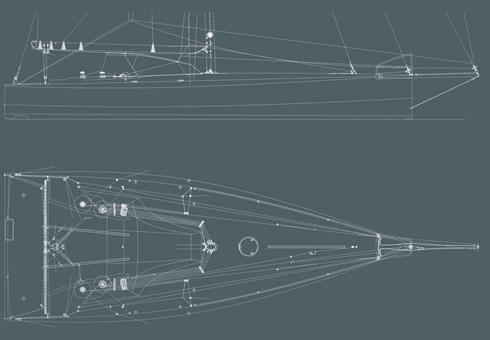

An even more complex set of calculations is necessary when it comes to the mast, which must support the power of the sails through the supporting cables called “shrouds.” There are many calculations to consider in how the shrouds spread the loads across the entire hull. All this has to be worked out so the boat and mast won’t fail in a powerful storm, yet still remain light enough to be competitive on the racecourse. There are always trade-offs to consider between strength and weight when making these important calculations and decisions.

An even more complex set of calculations is necessary when it comes to the mast, which must support the power of the sails through the supporting cables called “shrouds.” There are many calculations to consider in how the shrouds spread the loads across the entire hull. All this has to be worked out so the boat and mast won’t fail in a powerful storm, yet still remain light enough to be competitive on the racecourse. There are always trade-offs to consider between strength and weight when making these important calculations and decisions.

When the body of the boat is complete, the real fun can begin. The mast and boom, the sails and the rigging are mounted and the boat is launched. Finally, it’s time to take it test sailing to see how the sailplan and the rest of the boat work together.

When the body of the boat is complete, the real fun can begin. The mast and boom, the sails and the rigging are mounted and the boat is launched. Finally, it’s time to take it test sailing to see how the sailplan and the rest of the boat work together.