While maintenance and repair work continues on Bodacious Dream here in Wellington, I’ve found some time to review the many hours of Leg 2 video and photos I took on the voyage here from Cape Town, S.A.

It’s a Very Wavy World Out There – 42.568808S, 120.320942E

As you may recall, during that 7000-mile leg, we encountered quite a few tenacious storms – or what the weather people call “strong frontal passages.” I compiled some video clips from some of the storms into two briefer and more watchable pieces. I did some simple edits on them … which is all I can manage at the moment. Maybe soon, we can do a cool edit, but even without a thrilling musical soundtrack, you should still be able to get a feel for what it’s like out there on the open ocean when the winds and seas are “up.”

At the same time you are experiencing loneliness and fatigue, you are also carried along by something both energizing and mesmerizing.

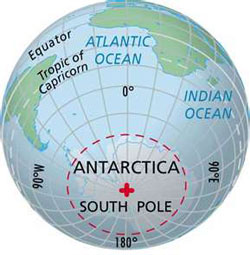

To remind you, these cold fronts blew up from the South (Antarctic) and progressed westward providing us with westerly winds that pushed us towards New Zealand. They generally announce themselves by a couple days of northwest wind, which then builds into the 30-knot range as the front passes through, after which the winds switch over to the southwest before gradually fading out.

One particularly interesting storm I wrote about previously, involved a spin-off of a low-pressure system from a cyclone, which teamed up with a passing cold front to amp up the winds and make our sailing a couple levels more extreme. While the strongest part of this front/low passed rather quickly over a 24-hour period, it was a week-long event of sailing as fast and as far east as we could to get in front of its path, so it could push us along instead of smacking us in the face. In the end, we did make it east of the storm, but just barely. During the height of the storm, we were clocking winds around 50 knots – and you’ll see in one of the video clips, the TWS (True Wind Speed) reading on the instrument panel showed gusts to 40 knots!

One particularly interesting storm I wrote about previously, involved a spin-off of a low-pressure system from a cyclone, which teamed up with a passing cold front to amp up the winds and make our sailing a couple levels more extreme. While the strongest part of this front/low passed rather quickly over a 24-hour period, it was a week-long event of sailing as fast and as far east as we could to get in front of its path, so it could push us along instead of smacking us in the face. In the end, we did make it east of the storm, but just barely. During the height of the storm, we were clocking winds around 50 knots – and you’ll see in one of the video clips, the TWS (True Wind Speed) reading on the instrument panel showed gusts to 40 knots!

No matter how senseless and arrogant we humans are about using up the ocean’s resources and wasting its precious beauty, it’s hard not to think that it is the ocean that will have the final word.

While all of this seems a bit edgy to the uninitiated, rest assured that Bodacious Dream is designed and built to handle these conditions, and in fact, is much more adept at it than I am! It’s specialized and custom-built for such tasks, whereas we humans are generalists who must keep adapting by learning new tricks. At the same time that the tempest tosses you around like a toy, you can’t help but succumb to the storm’s seductive beauty. To be in the center of such oceanic intensity, all the while knowing that there is so much more potential scale and force there yet to be unleashed, is humbling to say the least.

Coming up next, in a few days, will be some video that shows another side of Earth’s majestic powers. I’m talking about the glaciers of South Island, New Zealand. Stay tuned for that, as I think my visit to the glaciers was one of the most awe-inspiring experiences of my life.

Hope you enjoy the videos. I have a lot more footage and will try to compile them into more videos for those of you that have the time to watch.

Thanks and more soon….

– Dave

P.S. As a bonus for those of you who consider yourselves “veterans” of the sea, I have included another video of around 6 minutes in length that is mostly me talking through a week of strategic adjustments that I had to make in order to deal with the storm.

A sailor’s way of thinking about storms