By the time you read this, I will have landed in Panama and commenced the next phase of the journey… traversing through the Panama Canal.

By the time you read this, I will have landed in Panama and commenced the next phase of the journey… traversing through the Panama Canal.

From the amount of large shipping traffic I have been seeing the last few days, I fully expect the experience to be very different from that of the Galapagos Islands, where so much work is being done to better understand, research and protect the islands.

Here in Panama, over 100 years ago, it was of the highest importance for the governments of the world to find a quicker and safer passage between the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. The amazing canal that was created up and over the wild Isthmus of Panama profoundly changed the course of world commerce, travel and development. Both of these desires – the one to preserve nature as it is, and the other to remake nature to human purposes, are important – though oftentimes, they stand at opposite ends of a lively and ongoing debate.

So by now, you have hopefully had a chance to check out Tegan’s excellent Science Notes on the Galapagos. Before I begin to explore Panama, I have a few more observations to share on the Galapagos.

While I have sent along updates on my initial visit to the Charles Darwin Research Station, and my subsequent visit to North Seymour Island… not to mention my close encounter of the near disastrous kind… my time on the Galapagos Islands also provided me the opportunity to meet quite a few interesting people and to learn something about their particularly unique and passionate pursuits.

While visiting the cafés of Santa Cruz in the evenings, I met turtle experts, tour guides, and other global citizens, not so different from myself… as well as several scientist/sailors who were researching local sea life.

One interesting encounter was with a crew member with the Sea Shepherd organization, widely known for their activist opposition to commercial whaling, who educated me as to some of the organization’s less publicized efforts. As regards the Galapagos specifically, Sea Shepherd has given assistance to local authorities in two different areas; the first was in providing trained sniffing dogs to detect the illegal smuggling of exotic pets like iguanas and sea cucumbers, and secondly, by providing local commercial fishermen with AIS (Automatic Identification System) transmitters so that the authorities, as well as other local fishermen operating legally, can better enforce fishing regulations in their territorial waters and thus better promote the health and vitality of the regional fishing stock.

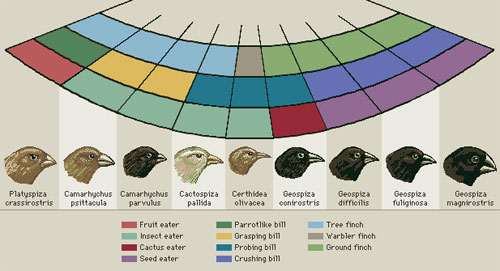

As Tegan explains in her report, there have for long been a variety of research projects going on in the Galapagos. She points us to one that our colleagues at Earthwatch are undertaking with the island’s famous Darwin finches.

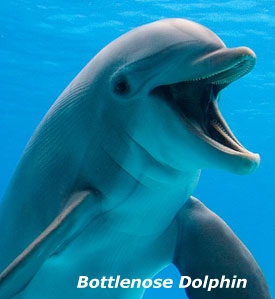

Once in Panama, we will be close to another great Earthwatch Research project – this one involved in safeguarding whales and dolphins in a still remote southern bay of Western Costa Rica, with the intent of protecting them when tourism starts to expand in that area. The project monitors three species of cetaceans in the gulf: the pantropical spotted dolphin, the bottlenose dolphin, and the humpback whale. By focusing on these cetacean species, they hope to gain knowledge on how to more effectively preserve this beautiful marine ecosystem.

Once in Panama, we will be close to another great Earthwatch Research project – this one involved in safeguarding whales and dolphins in a still remote southern bay of Western Costa Rica, with the intent of protecting them when tourism starts to expand in that area. The project monitors three species of cetaceans in the gulf: the pantropical spotted dolphin, the bottlenose dolphin, and the humpback whale. By focusing on these cetacean species, they hope to gain knowledge on how to more effectively preserve this beautiful marine ecosystem.

While the Galapagos are a special place that has in recent times become a “hot” destination for the eco-tourism industry, the fact is that places just like the Galapagos exist in one form or another just about everywhere in the world. Most, if not all of these under-developed areas are under similar pressures to withstand the immense pressures put upon the local environment and their populations.

Think about the Galapagos going from 600 residents to 20,000 in less than four decades all the while working to accommodate the growing stream of tourists that come – all of whom need food, lodging and services. Imagine the effect this has on indigenous populations and their traditions, which can easily be overwhelmed by such demands.

One last memory of my time on the Galapagos I would like to share. Last week at the end of a long day working on the boat (and in the rain…) I found myself growing increasingly frustrated with how long it was taking me to get things done. At the end of the workday, as I stepped off the water taxi, I suddenly knew I had to take a walk to Turtle Bay – some 40 minutes away. I had only an hour before public access to the beach was to close, so I hurried off.

The hike took me through a broad patch of cactus and trees, then through low brush and across lava fields at which point, l cleared a rise where ahead of me opened up one of the cleanest and longest stretches of white sand beach I have ever seen.

With only a few moments until I had to turn around and walk back, I dug my feet in the sand and watched as surfers rode the waves, hikers walked along the beach, photographers with extra long lenses looked for epic photographs and ghost crabs played tag with the waves and with each other. In just a few minutes’ time, all the frustrations of the day evaporated, and I found myself tucked under nature’s wing … preserved there at the shifting border between sea and shore.

Turtle Beach – Santa Cruz Island – Galapagos

It struck me in that moment how very important it is that places such as Turtle Beach be allowed to exist – specifically such places that still ROAR with a natural beauty that has not yet been compromised and transformed by commercial development, excessive tourism or resource extraction.

How can we keep these places as natural and undisturbed as possible yet still allow them to be publicly available to all? How can we maintain their raw and yet fragile beauty so that they might remain pristine for generations to come?

It’s places like Turtle Bay that help to keep us in touch with our natural world – and with our natural selves! We are not separate from the natural world. Rather we are an absolutely integral part of it – the world’s fate is our fate. As the great Henry David Thoreau famously wrote… ”In wildness is the preservation of the world.”

As the miles click off behind me and I near my transit of the Panama Canal, I come to the close of my time traversing the Pacific Ocean. I know that the crossing of the Canal will be another amazing experience and of an entirely different nature than any that has come before it… but an experience entirely new and unexpected I know it will be… which I suppose is what people like myself awaken each morning intent upon experiencing.

– Dave, Bodacious Dream and (the ready-for-anything) Franklin

:: BDX Website :: Email List Sign-Up :: Explorer Guides :: BDX Facebook