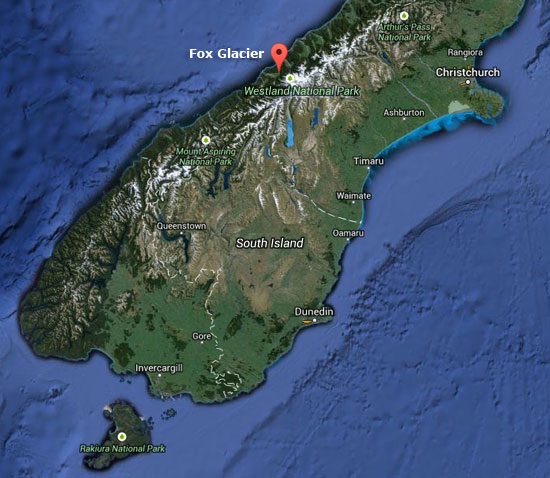

Dave Rearick: As promised, here’s the second half of our Glacier Report, the first part of which with my notes, photos and videos of my trip to Fox Glacier is viewable HERE!

Dave Rearick: As promised, here’s the second half of our Glacier Report, the first part of which with my notes, photos and videos of my trip to Fox Glacier is viewable HERE!

Today’s follow-up post, from our Earthwatch Scientist, Tegan Mortimer summarizes much of what science has learned about glaciers. Tegan knows a lot about glaciers, so I encourage you to read on and learn more about this important subject.

And if you would like to share these learnings with those younger than yourself, be sure to check out our new (and easily printable) Explorer Guide on Glaciers – or engage Tegan or I with questions via email.

So, take it away, Tegan!

_______________________________________________________________

1. The Power of Ice: Discovering the Glacial Landscape

Tegan Mortimer: Did you know that Charles Darwin was a geologist? Many of the thoughts in his most famous work, The Origin of Species were influenced by early discoveries in geomorphology – a field of science which tries to explain how landscapes change based on the pressures placed upon them. Ice is one of the greatest creators of landscapes. Just as Dave described the Great Lakes being carved out by glaciers in his previous post, in that same way was Cape Cod along with many other features of my native Massachusetts coastline also carved out by glaciers. When you really look closer, it’s possible to discover much of the history of a landscape by the way it looks today.

Tegan Mortimer: Did you know that Charles Darwin was a geologist? Many of the thoughts in his most famous work, The Origin of Species were influenced by early discoveries in geomorphology – a field of science which tries to explain how landscapes change based on the pressures placed upon them. Ice is one of the greatest creators of landscapes. Just as Dave described the Great Lakes being carved out by glaciers in his previous post, in that same way was Cape Cod along with many other features of my native Massachusetts coastline also carved out by glaciers. When you really look closer, it’s possible to discover much of the history of a landscape by the way it looks today.

The photo below is of a place in North Wales called Cwm Idwal (in Welsh a “w” is a vowel and is pronounced like “oo”) in the Glyderau Mountains.

Cwm Idal in the Glyderai Mountains of North Wales

Cwm Idal in the Glyderai Mountains of North Wales

Charles Darwin visited Cwm Idwal in 1831 to study the many fossils of ancient marine life that were found in its rocks. What they showed was that this land was once the bottom of the sea! For Darwin and his fellow geologists who were trying to show that landscapes could be shaped and changed in this way, these findings were so exciting that they somehow missed something even bigger!

It was another 10 years before Darwin returned to Cwm Idwal and this time he noticed the very obvious evidence of glaciation on the landscape. Cwm Idwal is what geologists call a “hanging valley” (alternately called a cirque, or a corrie or a cwm), which is the area from which a mountain glacier originates. Below Cwm Idwal, stretches a wide glacial U-shaped valley, which reaches all the way to current sea level. Cwm Idwal and the surrounding area are a wonderful example of “typical” glacial features.

2. How glaciers change the landscape

Glaciers and ice sheets form landscapes through two methods. The first happens when glaciers erode the landscape by scraping up the soil and bedrock after which they then deposit this material in other places.

Depending on the type of rock that a glacier is moving over, different glacial features will be left behind. Soft rocks like sandstone or limestone are easily ground up by the pressure of the ice, while harder rocks like granite are usually eroded through a process called “plucking.” What happens here is that water from the glacier melts into cracks in the rocks which than refreezes. As the ice in the glacier moves, it plucks away pieces of rock which are then trapped in the ice. Water expands when it freezes and is capable of further breaking apart rocks in what is called “freeze-thaw weathering.”

Depending on the type of rock that a glacier is moving over, different glacial features will be left behind. Soft rocks like sandstone or limestone are easily ground up by the pressure of the ice, while harder rocks like granite are usually eroded through a process called “plucking.” What happens here is that water from the glacier melts into cracks in the rocks which than refreezes. As the ice in the glacier moves, it plucks away pieces of rock which are then trapped in the ice. Water expands when it freezes and is capable of further breaking apart rocks in what is called “freeze-thaw weathering.”

(:: For a fun sidetrip, explore Fox Glacier via Google Earth by clicking on this link or the image above!)

The second method of erosion results in a roche moutonnée or a whaleback, which is an area of exposed bedrock, which has a smooth gently-sloped side and a steep vertical side. The photo below shows a few roche moutonnées which are only a few feet tall, though it is possible to see very large ones as well. Based on the direction of the sloping and angle of the sides you can tell which direction the glacier was moving. Remember that fact, as it will come up again later. The sloping side is the direction the glacier was coming from and the ice grinds down that side of the rock. The steeper sided angle is the direction the glacier was going and here is where that process called plucking happens. The tops of roche moutonnées often have scratches called striations which are horizontal scape marks from the rocks and debris in the ice.

Another erosional feature is called a crag and tail which is a tall hill usually with exposed rock and a gently sloping tail of softer rock behind it. In this case, the steep side of the hill is the direction that the glacier came from. The most famous crag and tail is Edinburgh Castle (pictured to the left) in Edinburgh, Scotland. The crag in a crag and tail is an area of very hard rock, usually a volcanic plug which forms when magma cools inside the vent of a volcano creating a column of very hard rock. When the glacier hits this rock, it can’t erode it, so it is forced to flow around the plug like water flowing around rocks in a stream. The plug protects the softer rock behind it leading to the formation of the tail.

Another erosional feature is called a crag and tail which is a tall hill usually with exposed rock and a gently sloping tail of softer rock behind it. In this case, the steep side of the hill is the direction that the glacier came from. The most famous crag and tail is Edinburgh Castle (pictured to the left) in Edinburgh, Scotland. The crag in a crag and tail is an area of very hard rock, usually a volcanic plug which forms when magma cools inside the vent of a volcano creating a column of very hard rock. When the glacier hits this rock, it can’t erode it, so it is forced to flow around the plug like water flowing around rocks in a stream. The plug protects the softer rock behind it leading to the formation of the tail.

All that eroded material has to go somewhere, so it is that glaciers leave behind particular landforms made up of all that “stuff.” Sediment left behind by glaciers is usually called till, which is made up of sand and gravel and rocks of every size. Erratics are large rocks like the photo below which are left behind by a retreating glacier. Geologists study the mineral structure of erratics to learn where they come from and learn more about the behavior of glaciers and ice sheets.

Glaciers push up ridges of material which are called moraines. These ridges can be formed at the base of the glacier which are called terminal moraines or at the edges of the glacier which are called lateral moraines. Cape Cod and Long Island on the US east coast are areas which have a series of terminal moraines formed thousands of years ago by the Laurentide ice sheet. As a glacier retreats, it can leave behind a series of terminal moraines which reflect the extent of the ice at different periods. Sometimes meltwater from a glacier will be kept from exiting a valley by a terminal moraine and will form a lake.

3. Glaciers Today

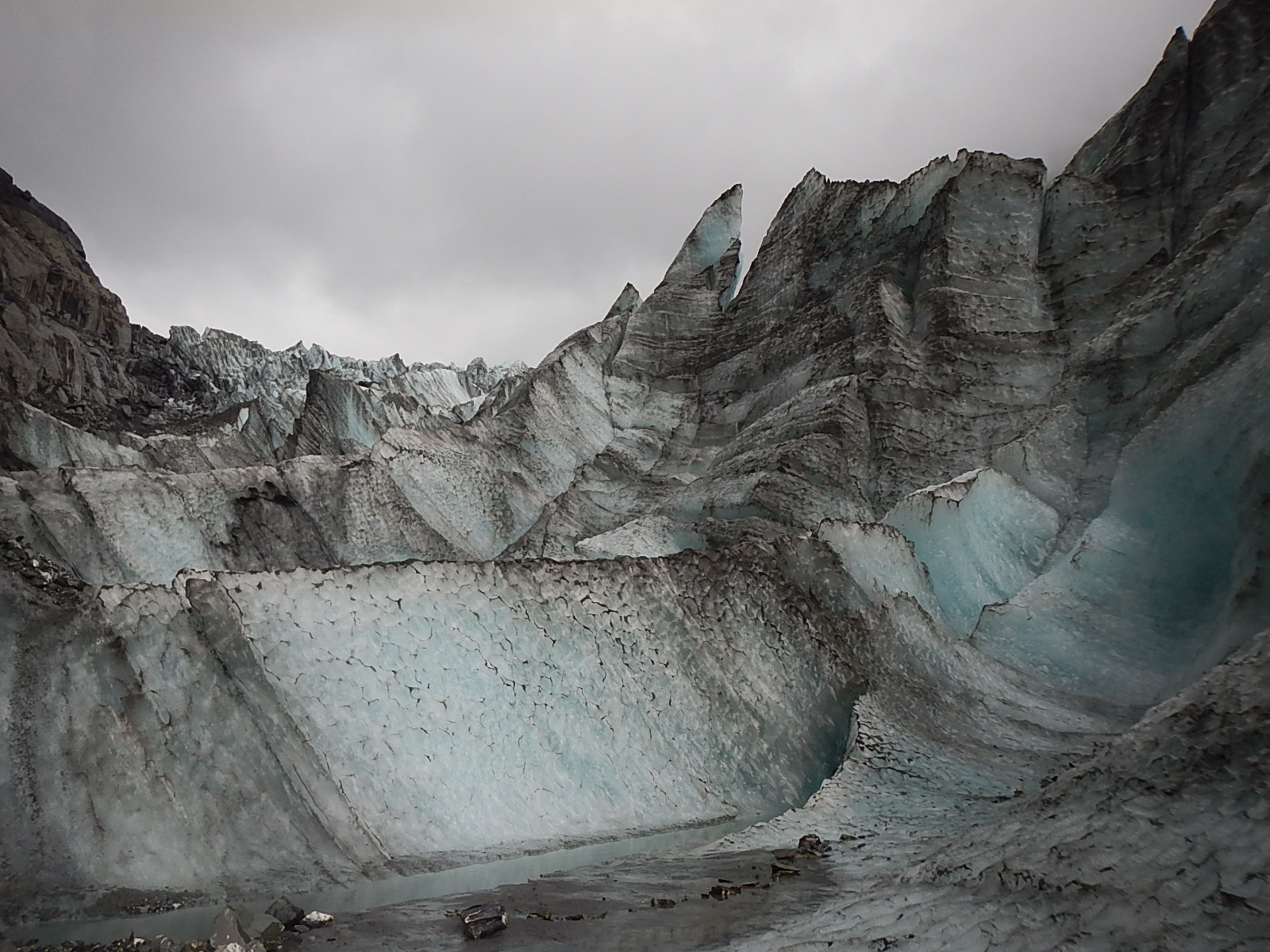

So what exactly is a glacier? Dave explained it pretty well; a glacier is essentially a river of ice. A river of ice? Since you can’t see it moving, how can that be? The fact is that glaciers are always on the move. The immense weight of the ice in a glacier causes it to deform internally, which results in unstoppable movement. Gravity and meltwater underneath the glacier can also help it to move downslope. The areas at the edges of the glacier are under less pressure so this is where great cracks in the ice called crevasses form. When pieces of a glacier fall off the base of the glacier it is call calving – which is happening lately at a much increased rate. Here is an incredible high-def clip from a recent movie called “Chasing Ice” that records the longest and biggest calving ever recorded.

We know Fox Glacier is retreating, so how then is it moving downhill? The growth of a glacier is based on something called mass balance. Snow falls on the top of the glacier and freezes while ice from the bottom of the glacier melts or breaks off, a process that is called ablation. As long as the accumulation at the top outweighs the ablation at the bottom, the glacier will grow. However, if the ablation outweighs the accumulation, then the glacier will retreat. This is the case of the Fox Glacier, and unfortunately the case for many glaciers around the world.

4. Does it really matter if the glaciers disappear?

It would most certainly be a tragedy if alpine glaciers were to disappear due to the effects of human climate change. They are majestic places to behold and also provide revenue from tourism to areas in these regions. However, and more importantly, glaciers also provide huge stores of fresh water, which are released throughout the year. For example, about 1.3 billion people depend on Himalayan glaciers for drinking water and other water needs. If these resources were to disappear, it would have devastating effects on human populations.

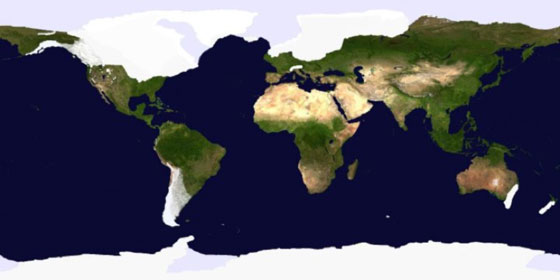

5. Glaciers of the Past

At times throughout Earth’s history, huge swathes of the planet have been covered by ice. We know that some of these ice sheets covered thousands of miles and could be several miles thick. Such ice ages can last for millions of years and go through a series of glacial and interglacial periods where ice cover increases and decreases. The last ice age started 2.6 million years ago and is still ongoing today. We are currently in an interglacial period called the Holocene, which started 12,000 years ago. When people talk about the “Ice Age” they are usually talking about the previous glacial period, which occurred from 110,000 to 12,000 years ago. The ice was at its greatest expanse just 22,000 years ago when most of the northern half of North America and northern Europe and Asia were covered in ice. In the Southern Hemisphere, the Andes in South America and Southern Alps in New Zealand had large ice caps as well.

The glaciated landscapes of North America, Europe, South America, and New Zealand were formed during this Ice Age.

The glaciated landscapes of North America, Europe, South America, and New Zealand were formed during this Ice Age.

6. What happens when massive ice sheets disappear?

The most important thing to remember is that ice sheets (and glaciers) hold a huge amount of water. The sea level was about 120 meters lower during the last glacial period than it is today. We still have two major ice sheets on earth, the Antarctic Ice Sheet and the Greenland Ice Sheet. If these were to melt – which they give every indication of doing, and quite rapidly, we would see increases to sea level, which would threaten many coastal cities and sea-dependent communities across the globe.

See all Dave’s photos and videos from Fox Glacier right HERE!

– Tegan

:: Tegan Mortimer is a scientist with Earthwatch Institute. For more exciting science insights, check out our BDX Explorer Guides or stop by our Citizen Science Resources page, where you can also find all of Tegan’s previous “Science Notes.”

We welcome your input or participation on our BDX Learning & Discovery efforts. You can always reach us here or via email.