Another run of exceptional days out here in the Southern Ocean – two cold fronts in two days, our first lightning storms … not to mention a kelp attack, close encounters of the “bird” kind and an utterly amazing experience with bioluminescence.

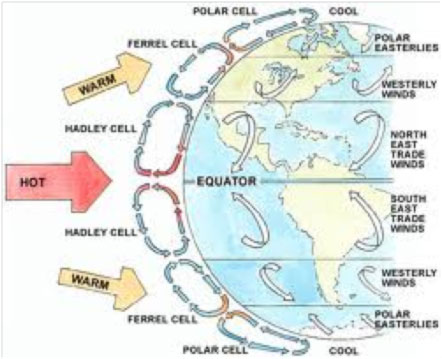

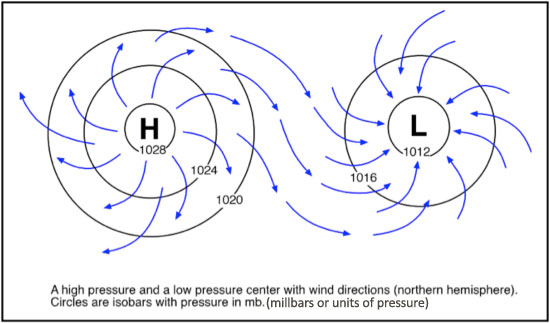

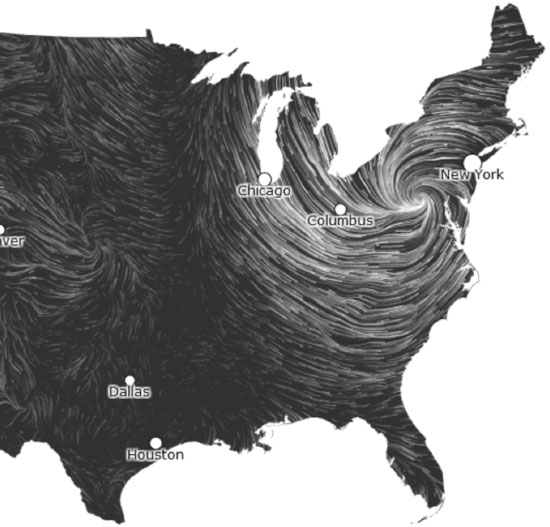

The two back-to-back cold fronts began last Sunday night. The first one arrived in typical fashion, riding in on a northwest wind, but the second came in with a headwind that took forever to switch back over to the northwest, which was fine by me as it put the wind behind us and made the sailing easier. Once it did switch though, it brought along with it lightning and thunderstorms. I had not seen lightning in these squalls before, so it made for an interesting (and dramatic) night. Eventually both cold fronts and their stormy winds passed, leaving us with good winds for racking up some good miles.

1300 Miles to Port – 45.35797S, 148.83321E

1300 Miles to Port – 45.35797S, 148.83321E

As I write this, I’m just passing under Tasmania at about 45.5 South Latitude and setting my cross-hairs on the southernmost tip of the South Island of New Zealand! That waypoint, at about 155 East Longitude is just about 600 miles away, but there’s still a lot of sailing as the course to Wellington travels up the South Island and then down the Cook Strait. By my estimate, there’s still over 1300 miles left to the end of Leg 2 … but isn’t that cool? I figure, since leaving Jamestown, Rhode Island on October 2nd, I’ve sailed over 15,000 miles! I’m still hoping by the 10th of February to be tied up at Chaffer’s Marina in Wellington, New Zealand, and celebrating my return to Terra Firma.

Now, when I say KELP attack, I probably should have said kelp “attach!” The other morning, just after the second cold front, I began to feel that something was slowing down the boat. That’s the sort of learned intuition one gets around boats. You sometimes sense it before you have any idea what it might be. I finally looked aft and saw a long brown object dragging off the starboard rudder. I hooked up my tether and reached over the side to grab onto it and pulled as hard as I could but got no release. This one was tenacious, but after several attempts, I was finally able to dislodge it. Here’s a picture of it.

Encrusted kelp – 42.5441046S, 134.5444664E

For a few moments, I thought that maybe it was a piece of waste rubber, but it was obviously kelp. Upon further inspection, I found it was laced with some sort of crustaceans that were incredibly beautiful in their simplicity and in their subtle color shading. Here’s a picture of them.

Something special, wouldn’t you say? – 42.5441046S, 134.5444664E

Having never seen anything quite like it before, I could not help but marvel once again at nature’s infinitely fertile ability to manifest life forms of such diverse and inexplicable beauty. Now, I wonder if anyone can tell us more specifically what type of crustaceans these might be? (My best guesses to the questions I pose here are all down below.)

Now as to the BIRDS, for the past week or so, this very interesting group of birds has been regularly circling the boat. I’ve watched them for endless hours, entranced by their curious flight patterns. They aren’t big birds; one would probably fit in the palm of my hand. They have a white band around their mid-section, but what captures your attention is the way in which they fly. Swooping up and over waves, but getting right down to the water and then seeming to dip their right wing in the water, time and time again. Darting up and down in quick motions … it almost looked as if they had a dysfunctional wing.

Now I figured there was some sort of feeding action going on, but I couldn’t tell exactly what, even though I watched for days on end. I did start to notice that they occasionally dipped the left wing too, so maybe it was just a matter of convenience relative to their stalking food. Even after days of watching them, I find it hard to take my eyes off of them. But here’s a picture of one of them about to dip his or her wing. Anyone want to take a guess as to what kind of bird these are?

As close to constant companions as I get for now – 42.2220238S, 127.330546E

So, the other morning, after the last cold front passed, I was up on the foredeck making a sail change and noticed something unusual … tiny fly-like bugs on part of the deck. I wasn’t sure where they could have come from, but after a much closer look, I realized that what I was looking at were like very tiny shrimp, but no longer than a couple of millimeters. I thought these must be what the birds are catching as they swoop and dip into the waves. How about this species … anyone have a clue what they might be?

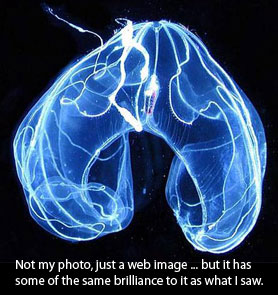

And as if both these creatures weren’t fantastical enough, the other night, an explosion of bioluminescence proved as spectacular as any I’ve ever seen in all my years at sea. As I typically do, I came up on deck to have a look around. It was pitch dark out and raining with some flashes of lightning off to the north. At first look I panicked … thinking I was seeing the stern light of a ship just in front of me. (In case you’re curious, I haven’t seen another ship for about four or five weeks now.)

And as if both these creatures weren’t fantastical enough, the other night, an explosion of bioluminescence proved as spectacular as any I’ve ever seen in all my years at sea. As I typically do, I came up on deck to have a look around. It was pitch dark out and raining with some flashes of lightning off to the north. At first look I panicked … thinking I was seeing the stern light of a ship just in front of me. (In case you’re curious, I haven’t seen another ship for about four or five weeks now.)

As my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I realized what I was seeing. The sea was alive! Every wave top, every white cap was glowing whitish green. The wake from the boat was looking like I had a light on under the boat. The trails from the rudders looked like luminous streamers flying from a circus tent flagpole. Most amazing of all were these floating orbs, glowing bright in the water … and not just one orb, there many all around me! At one point, I counted 20 or more behind the boat and you could see them for quite a ways away… constant in their gleaming brightness.

On each side of the boat, there was this same density of bioluminescence. Quite the surrealistic event, I can assure you – sailing along at 10 knots, all alone in the black of night, thousands of miles away from anywhere, in the middle of a thunderstorm and rain … with this incredible beauty erupting all around me. I’ve been back out every night since looking for them, but nothing more so far. I suspect that night was so uniquely spectacular because of conditions that followed from the electrical storm and the super-charged air.

On each side of the boat, there was this same density of bioluminescence. Quite the surrealistic event, I can assure you – sailing along at 10 knots, all alone in the black of night, thousands of miles away from anywhere, in the middle of a thunderstorm and rain … with this incredible beauty erupting all around me. I’ve been back out every night since looking for them, but nothing more so far. I suspect that night was so uniquely spectacular because of conditions that followed from the electrical storm and the super-charged air.

On reflection it strikes me that the closer you get to the ocean, the more it reveals, the more you become part of its surface life. It is truly the great mother of wonder. It surrounds us, feeds us and cleanses the earth and the air. It also provides us with pathways to anywhere in the world and along the way, never stops teaching us and showing us sights and sounds even beyond our wildest imaginings. I so wish there was a way I could photograph this bioluminescence to show you all, but perhaps it’s one of those things you just have to see for yourself. I stood there for half an hour observing it all in the pouring rain. I was both soaked and stoked when I finally went back inside again.

:: (SPOILER ALERT! As to the QUESTIONS above, I shared my observations with Tegan Mortimer, our Earthwatch ocean science colleague for the Circumnavigation, and here are our combined best guesses as to what I saw.

- The creatures that attached to the kelp are called goose barnacles!

- The birds look to be gray-back storm petrels.

- The type of flying they do is something called “dynamic soaring,” which Tegan says she will soon be covering in a new science note about pelagic sea birds. (See Tegan’s previous science notes on our Citizen Science Resource Page here!)

- Strangely enough, if the birds are in fact gray-back storm petrels, they actually concentrate on feeding on the larvae of goose barnacles, so the tiny shrimp I saw on deck were likely that, which is what the petrels were stalking the whole time.

So, if our answers are correct, then all these sightings were actually interrelated, which gives me a special feeling of gratitude to be able to plumb a little deeper into nature’s mysterious and inter-connected cycles. ::

So onward towards New Zealand! Just another 7 to 10 days and I’ll get a chance to take a break, eat some real food, reconnect with old friends, restock the chocolate and cookie supply, as well as everything else, and begin to prepare Bodacious Dream for Leg 3 of this amazing journey.

I do hope you’re enjoying following along with these updates. I also hope you’ve had a chance to share the Explorer Guides with some young people in your lives or to look them over yourselves. There’s so much more to share and explore out here. Give me a few days once I arrive in New Zealand to get some of these amazing photos and videos up for you to see and enjoy! And here’s the link to the Email List Sign-Up.

But for now, it’s back to sailing. “Roll East Young Franklin, Roll East!”

– Dave, Bodacious Dream and (the well-weathered) Franklin