With Bodacious Dream back in the water in Wellington, a quick update from Dave followed below by an earlier but previously unpublished “science note” on African penguins from our ocean scientist colleague, Tegan Mortimer.

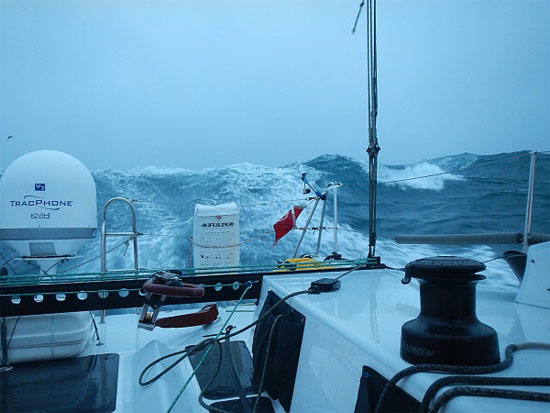

Dave Rearick: Wellington, NZ has a worldwide reputation for windy weather. For the past few days though, it has instead offered up absolutely gorgeous days of clear and sunny skies with winds at less than 15 knots. This has made for perfect conditions to test sail Bodacious Dream after the recent work and refit she just underwent. So far, everything is coming together just fine. Our awesome crew has done a great job getting Bo into shape for Leg 3! (See some pics below in slideshow format.)

Dave Rearick: Wellington, NZ has a worldwide reputation for windy weather. For the past few days though, it has instead offered up absolutely gorgeous days of clear and sunny skies with winds at less than 15 knots. This has made for perfect conditions to test sail Bodacious Dream after the recent work and refit she just underwent. So far, everything is coming together just fine. Our awesome crew has done a great job getting Bo into shape for Leg 3! (See some pics below in slideshow format.)

Today, we’ll begin the sorting and packing of the boat as forecasts are for wet and windy weather to return this weekend. Our hope after that front passes is to get the go-ahead weather window that we need to depart early next week!

Test sailing … Click the arrows to advance, and scroll over to read the captions.While we get ready for all that and I head off to do some major provisioning, we wanted to revisit some of Tegan Mortimer’s Science Notes, we didn’t have a chance to publish before now.

We are also readying a wonderfully informative science note on “Seabirds,” which includes a list of all the seabird sightings we’ve identified so far on the voyage. But before we do that, we want to focus in on one particular seabird that holds a special interest for people all over the world – and that’s penguins!

During our post-Leg 1 Cape Town stopover in December, we were treated to the unique experience of visiting a large colony of African penguins that reside near the Cape of Good Hope (the southernmost tip of Africa.) While the overall distance from there to Antarctica is pretty substantial, it is still within the habitat range for penguins, for reasons that Tegan will explain in her excellent report. And I’ll be back soon with more.

– Dave

Tegan Science Notes #5 – Penguins in Africa?

Tegan Science Notes #5 – Penguins in Africa?

When Dave and Bodacious Dream reached Cape Town and the end of Leg 1 of his circumnavigation at the beginning of the year, he took time to explore some of the many diverse natural wonders of that region.

One of his first trips was to see the penguins. Yes, you heard that right, penguins in Africa! The African penguin is only found along the west coast of South Africa and Namibia, though it is also one of the most common species kept by zoos and aquariums.

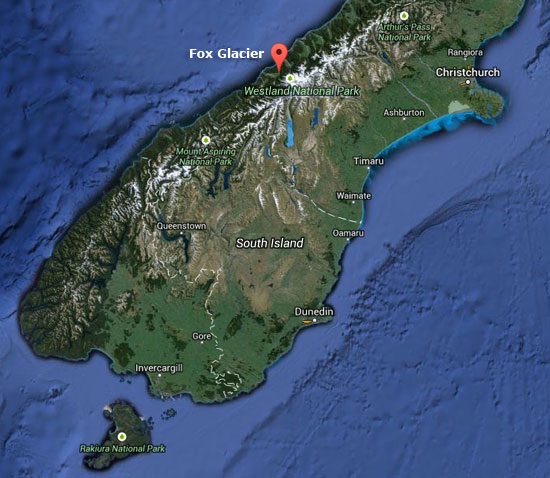

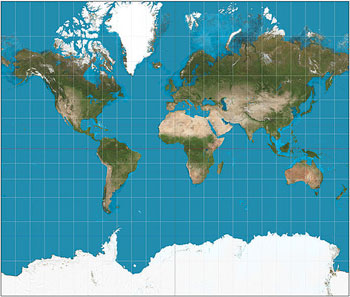

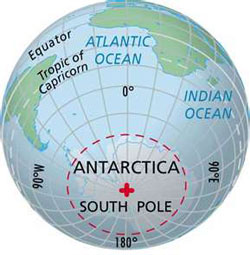

We usually think of penguins as only occurring in the snow and ice of Antarctica, but there are actually quite a few species that live in more temperate habitats along the coasts of South America, Australia, New Zealand and of course Africa. All species of penguins are native to the Southern Hemisphere, so you would never find penguins interacting with Northern Hemisphere species like polar bears and walruses.

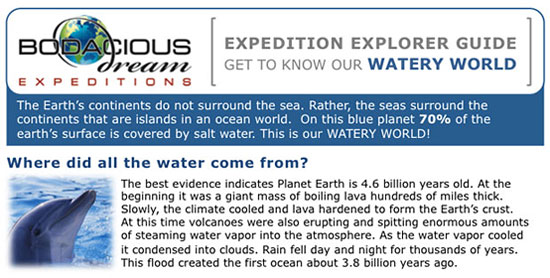

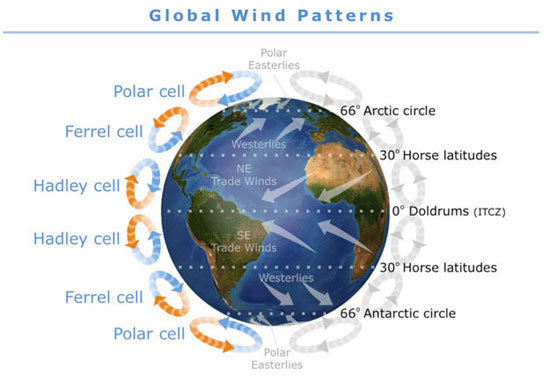

The areas in which penguins are found do have something in common though: cooler water. When we look at charts of surface water temperatures around South Africa, we see that there is colder water around the western coast of South Africa and Namibia, in exactly the area that African penguins are found. This is called the Benguela Current. This current carries cold water northwards and creates an upwelling zone near the coast. The South East trade winds then push the surface waters away from the coast which draws the deep cooler water up to the surface.

The areas in which penguins are found do have something in common though: cooler water. When we look at charts of surface water temperatures around South Africa, we see that there is colder water around the western coast of South Africa and Namibia, in exactly the area that African penguins are found. This is called the Benguela Current. This current carries cold water northwards and creates an upwelling zone near the coast. The South East trade winds then push the surface waters away from the coast which draws the deep cooler water up to the surface.

Cold water carries more oxygen and nutrients in it because it’s denser than warm water. When phytoplankton undergo photosynthesis, they use up nutrients and oxygen from the surface water; unless this surface water is replenished then photosynthesis will stop due to a lack of oxygen and nutrients. This is why upwelling is so important; it continually brings new oxygen and nutrient-rich waters to the surface. High levels of plankton support rich ecosystems of small schooling fish, krill and squid that then help sustain larger predators such as whales, sharks, and sea birds.

African penguins feed on small schooling fish, particularly sardines and anchovies which are supported in huge numbers by the Benguela Current ecosystem. Sardines and anchovies are some of the most important commercial fish species and are caught in large numbers throughout the world. In South Africa, penguins compete with fishermen for these precious fish.

Unfortunately African penguins are considered to be endangered. Their population has declined by about 60% in the last 30 years, which is a very rapid rate. It is thought that a lack of food is the major cause of the decline. This lack of fish is due to both the huge numbers that fishermen remove, as well as environmental fluctuations in fish numbers and distribution.

Earthwatch scientists are active in studying the nesting colonies present on Robben Island; trying to understand their rapid decline and formulate strategies, which will increase their chance of survival. One success so far seems to be the addition of artificial nesting boxes to the colony. These birds typically nest in burrows, but many of their nesting sites have had the naturally thick layer of guano removed for use as commercial fertilizer leaving nothing for the penguins to burrow into. Penguins now seem to actually prefer the nesting boxes, which allow them to be more successful at rearing chicks than if they were in a burrow or out in the open.

It is very easy in this instance to blame fishermen for catching too many fish, which reduces what is left behind for the penguins. It is true that many fishing practices are very destructive, both to fish populations and to the marine ecosystem, but it is also important to remember that the ocean is an ever-changing eco-system. If the lowest levels of the marine food chain (plankton and small school fish) change, we see changes in the higher levels too. Climate change is driving these changes, just as we humans are driving climate change. Everybody has the ability to make a difference by way of the choices we make every day. We all can help to save the African Penguin.

To close things off, here’s a cute internet video that shows the ups and downs of being a penguin.

– Tegan

:: Tegan Mortimer is a scientist with Earthwatch Institute. For more exciting science insights, check out our BDX Explorer Guides or stop by our Citizen Science Resources page, where you can also find all of Tegan’s previous “Science Notes.” We welcome your input or participation on our BDX Learning & Discovery efforts. You can always reach us here or @ <oceanexplorer@bodaciousdreamexpeditions.com>